Articles & Videos

The importance of productive struggle in maths

Categories

Subscribe to our newsletters

Receive teaching resources and tips, exclusive special offers, useful product information and more!

Back to Product Features articles & videos

The importance of productive struggle in maths

BitMaths 5/6/24

One of the biggest hurdles in maths education is encouraging students to persevere and engage in complex problems with confidence.

Although the teaching of mathematics is often associated with learning formulas and algorithms, the cultivation of social and emotional skills is equally as important for mathematical performance. Students who demonstrate perseverance and are adept at managing stress levels outperform their peers academically and are more engaged in learning.1 Students who have a growth mindset overcome negative attitudes concerning their perceived ability in maths and rise to a challenge more easily.2

What is productive struggle and why is it important?

Productive struggle describes the cognitive process by which a child tackles and engages with a complex problem to find meaning.3 When conducted in a safe learning environment, productive struggle can improve a student’s attitude towards maths and problem-solving, equipping them with skills to overcome obstacles, deepen conceptual understanding and build mathematical fluency.4

Ways to set up a classroom environment for productive struggle

Be upfront about the challenging nature of activities

For productive struggle to be valuable, make students aware that a challenge is coming and encourage them to adopt a positive mindset.5 Make it clear that you expect students to persevere but explain that all thinking related to the task is valuable, even if they don’t find a solution.

Praise perseverance and creative problem-solving over performance

To help develop a growth mindset, praise students for their effort, perseverance and creativity. By celebrating persistence over performance, students will see that mathematical ability is not fixed and can improve with effort and time. It also helps students to view setbacks or mistakes as learning opportunities.5

Give students plenty of time to grapple with a problem

Thinking requires time! Dedicate plenty of time for students to interpret a problem and implement a variety of ideas or strategies.

Encourage collaboration and discussion

Working together and sharing solutions and ideas helps students make connections, engage with the activity, develop social and emotional skills and piece together their own understanding. Share your own solution to a problem, explaining all mental steps in the process, and encourage students to do the same.6

Ways BitMaths can help you incorporate productive struggle in maths lessons

Choose activities that offer a suitable challenge

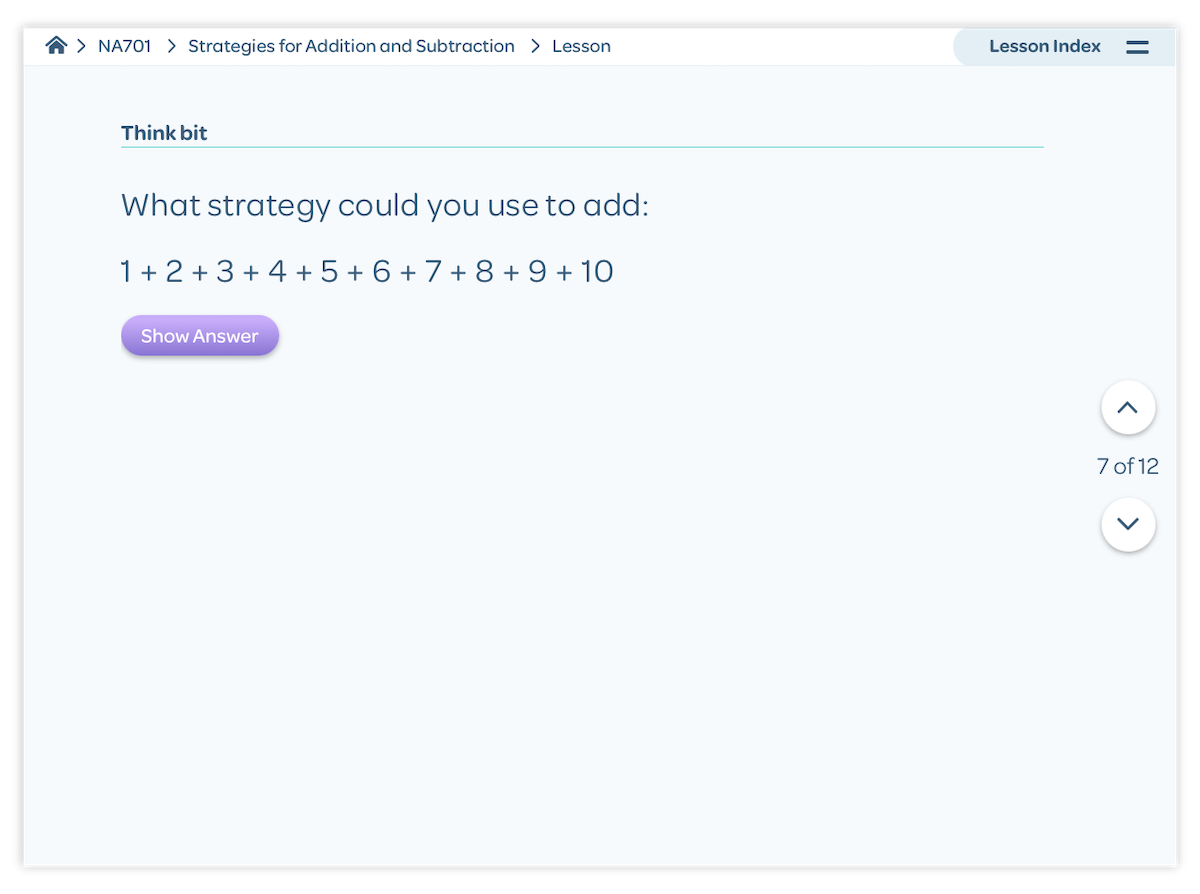

For whole class activities, use Think Bits. These are short but challenging thinking questions embedded in many of the teaching slideshows. With collaboration and discussion, these activities can help students compare ways of thinking and make connections with the maths concepts they’re working on.

Example of a Think Bit from BitMaths: NA701 The Four Operations (Australian Curriculum).

Example of a Think Bit from BitMaths: NA701 The Four Operations (Australian Curriculum).

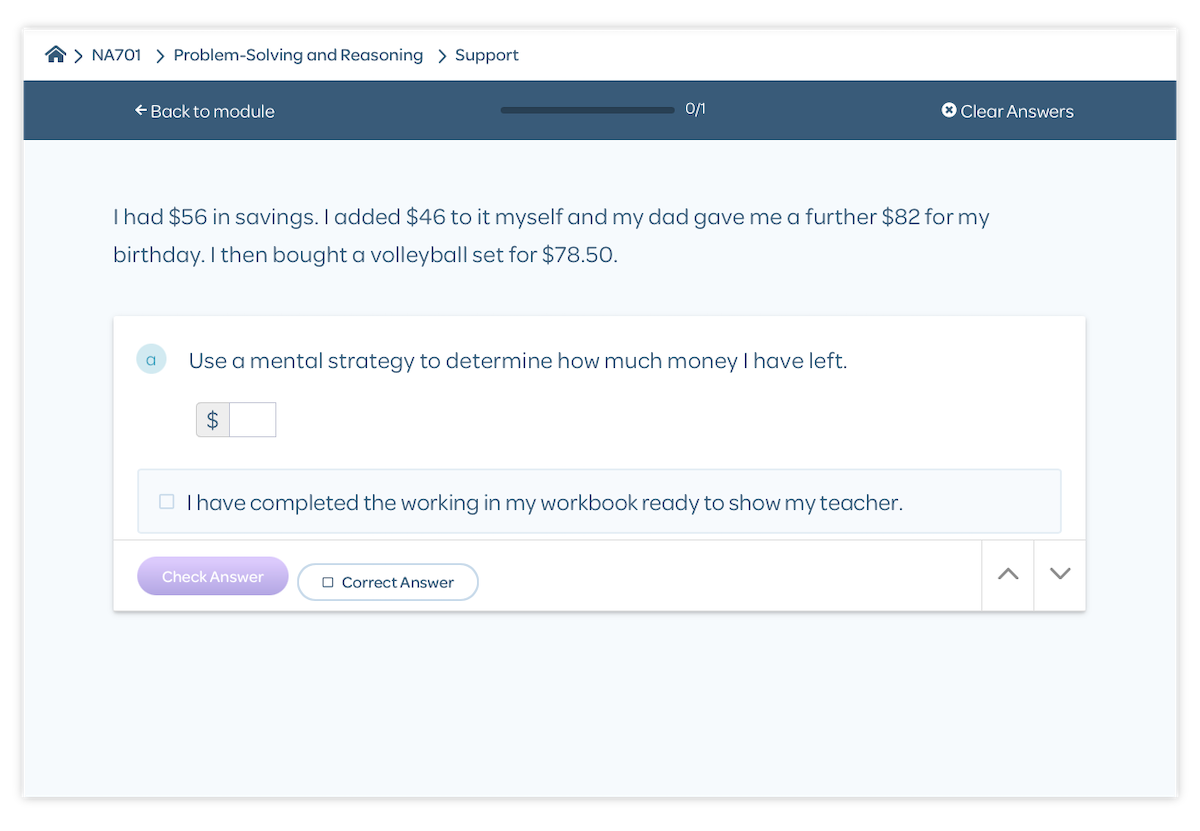

For individual activities, use the Independent Problem-Solving Activities. There are differentiated activities in all modules that provide opportunities for students to apply higher-order thinking skills. Select the level that offers an appropriate challenge for each student.

Example of an Independent Problem-Solving Activity from BitMaths: NA701 The Four Operations (Australian Curriculum).

Example of an Independent Problem-Solving Activity from BitMaths: NA701 The Four Operations (Australian Curriculum).

Ensure students are supported throughout the process

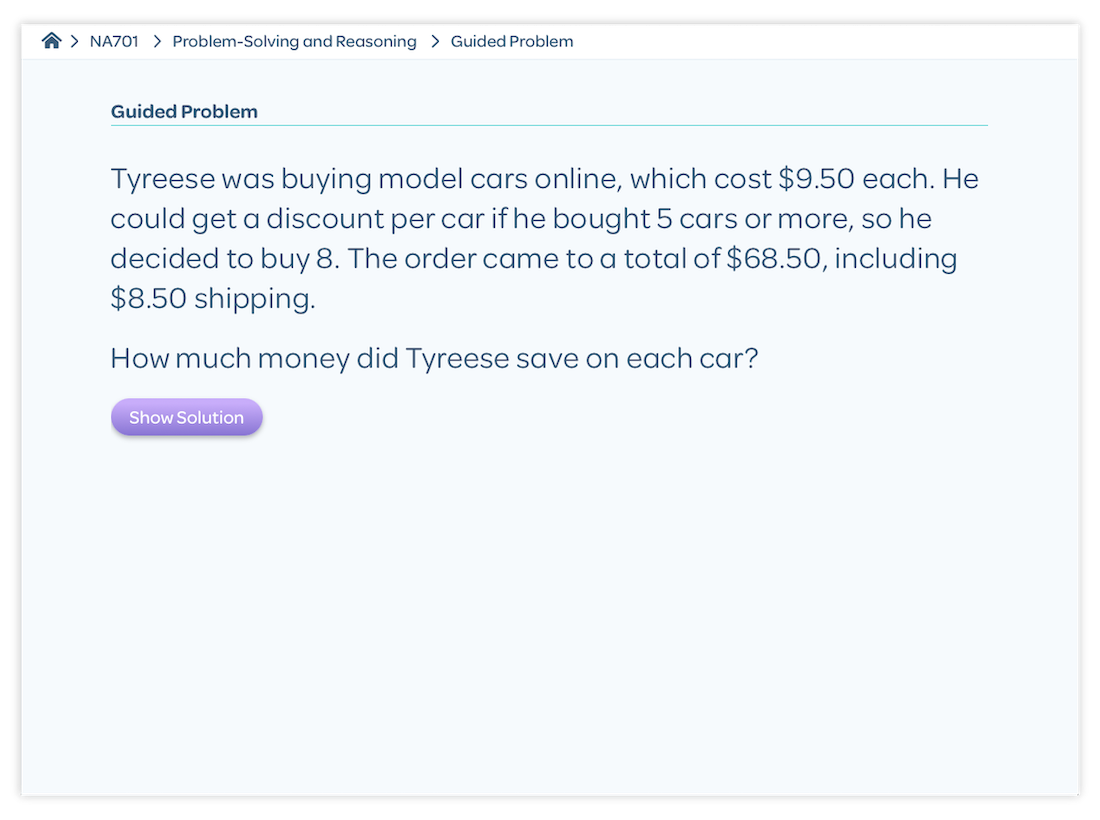

To align with Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development, an activity must be challenging but achievable with support.7 To help students prepare for productive struggle, use the Guided Problem-Solving Activities. These are whole class activities that act as an exemplar for the Independent Problem-Solving Activities.

Example of a Guided Problem-Solving Activity from BitMaths: NA701 The Four Operations (Australian Curriculum).

Example of a Guided Problem-Solving Activity from BitMaths: NA701 The Four Operations (Australian Curriculum).

Provide scaffolding without removing the obstacle

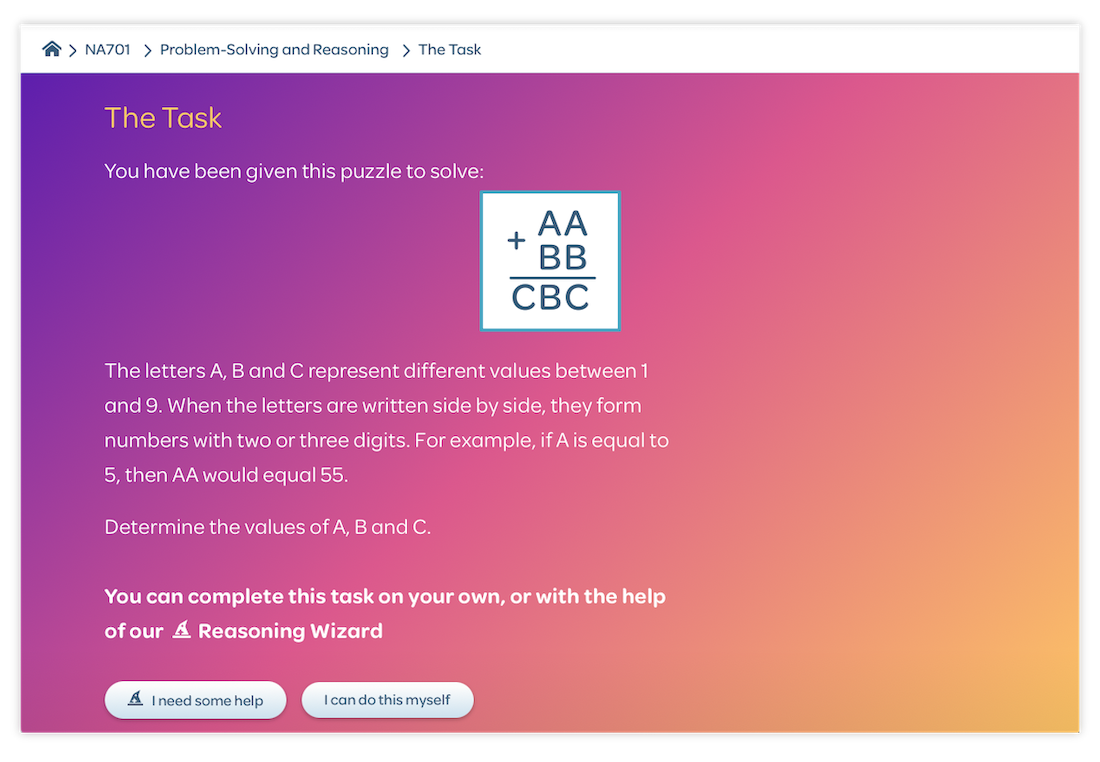

When students are struggling with a task, use careful questioning and prompting to encourage constructive thinking and help students consolidate their ideas. For self-guided independent tasks, encourage students to use the Reasoning Wizard found in all Reasoning Activities. The Reasoning Wizard carefully guides students through the thinking required to complete an activity without giving away the next steps in the process. It helps students focus on the how and why of the solution, rather than just the answer itself.

Example of a Reasoning Activity from BitMaths: NA701 The Four Operations (Australian Curriculum).

Example of a Reasoning Activity from BitMaths: NA701 The Four Operations (Australian Curriculum).

Supporting productive struggle is just one of the amazing benefits of the BitMaths program. There’s so much more to discover. Request a free trial today and explore for yourself!

References

Schleicher, A 2022, PISA 2022 Insights and interpretations, Report, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, viewed 21 May 2024, https://www.oecd.org/pisa/PISA 2022 Insights and Interpretations.pdf↩

Kaya, S & Karakoc 2022, ‘Math mindsets and academic grit: How are they related to primary math achievement?’, European Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, vol.10, no. 3, pp. 298-309, https://doi.org/10.30935/scimath/11881↩

DiNapoli, J 2021, ‘Investigating perseverance improvement in secondary mathematics students’, in E de Vries, Y Hod, & J Ahn (eds), Proceedings of the 15th International Conference of the Learning Sciences, ICLS 2021, pp. 871-872. Bochum, Germany: International Society of the Learning Sciences.↩

Murdoch, D, English, AR, Hintz, A & Tyson, K 2020, ‘Feeling heard: Inclusive education, transformative learning, and productive struggle’, Educational Theory, vol. 70, no. 5, pp. 525-679, https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12449↩

Dweck, CS & Yeager, DS 2021, ‘A Growth Mindset about Intelligence’, in GM Walton & AJ Crum (eds), Handbook of Wise Interventions, The Guilford Press, New York, pp.9-35.↩

Cai, J & Liking, R 2020, ‘Affect in mathematical problem posing: conceptualization, advances, and future directions for research’, Educational Studies in Mathematics, vol. 105, pp. 287-301, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-020-10008-x↩

Margolis, AA 2020, ‘Zone of Proximal Development, Scaffolding and Teaching Practice’, Cultural-Historical Psychology, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 15-26, https://doi.org/10.17759↩